So it happened yesterday. It being Borders finally filing for bankruptcy. If you've been keeping up with publishing news, this shouldn't have been surprising at all. I personally believe they hammered the final nail in the coffin when they decided not to get into the whole e-book game. Yes, they sold the Kobo and Sony readers, but neither of those were a Borders reader, not like how Barnes & Noble has the Nook. Anyway, it's certainly sad, though I know there are some people out there rejoicing. Yes, you know who I'm talking about. Some writers who have been having great success with their self-published e-books. I don't begrudge them anything, though it does get under my skin how some of these writers for years and years claimed to love booksellers, and would do anything for booksellers, but then, once it became clear they no longer needed booksellers, basically gave them all the finger. Yeah, that right there is a real douchebag move.

This PDF gives a list of all the Borders stores that are closing. Is your local Borders on it? My local Borders isn't, though I wonder why. Just the other night my wife and I were in there, and it was pretty deserted. We'd gotten an Olive Garden gift certificate so we had decided to, you know, go to Olive Garden, but the wait was pretty long as is expected on a weekend night. Luckily, there's a Borders right next door. The people who were there, it seemed, were just waiting for their Olive Garden buzzer to go off. I didn't really see anybody intent on buying books. Maybe that's because they didn't have the Hint Fiction anthology in stock, who knows.

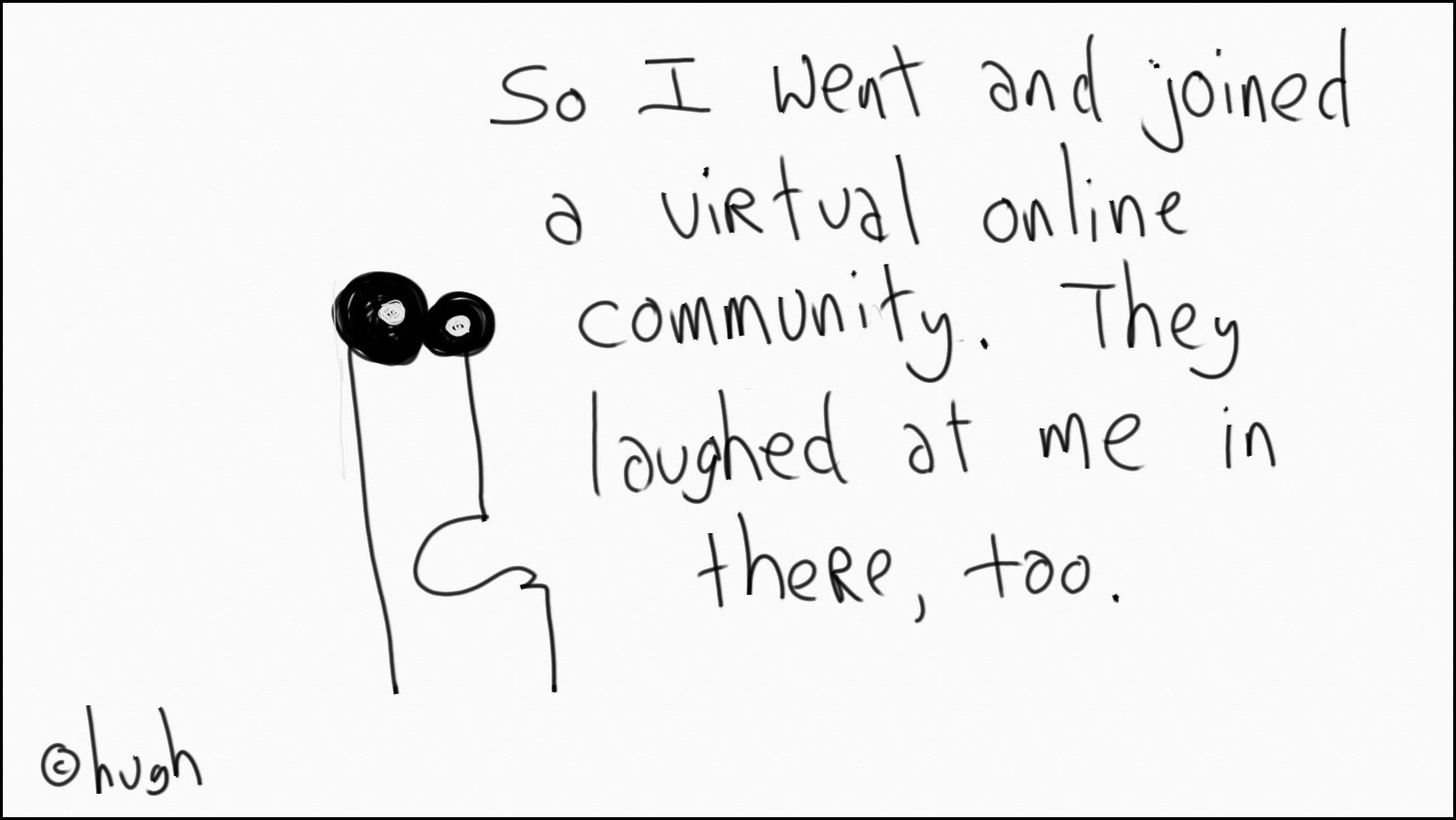

The other group of people were the ones occupying the cafe. Yes, you know the group I'm talking about. You might even be one of them. Yesterday Brian Keene posted what he thought was the real reason Borders filed for bankruptcy, and I have to say, it makes a lot of sense. Basically, people going in there to use the free WiFi and drink coffee and look at books but not actually buying any books.

Also yesterday Nick Mamatas posted an interesting anecdote on Facebook about his first novel Move Under Ground (which has just recently become available on Kindle):

Back when MOVE UNDER GROUND came out in paperback, the print run was based on a fairly large, if tentative, buy from Borders. The BGI buyer reversed course and actually bought zero copies, claiming that the book was "more sophisticated" than he was comfortable placing in the horror section.

A long time ago, publishes published the books they wanted to publish and the booksellers sold those books. Then, at some point, a shift began to occur, where the booksellers began to have more and more say over what the publishers published. Now, from what I understand, some publishers sometimes approach major booksellers first about a particular book to see if they would have interest in selling it before they even decide to publish it.

My supernatural thriller The Calling which I announced on Monday has the same sort of backstory. Basically, it's a complex novel in the Peter Straub vein. Peter Straub can get away with writing really complex novels because he's Peter Straub, but newer writers have a tougher time sliding them past publishers. There was a lot of great feedback from publishers on the novel who liked it but had to pass for various reasons, but the best (or worst?) was one editor saying she loved it but felt it was "way too complex for most readers."

And so such is life.

But what, exactly, constitutes "most readers"? It's really fascinating when you think about it. How Hollywood decides what audiences want to see, just as New York publishers decide what readers want to read. They say our culture is getting dumber and dumber, but who's to blame? Hollywood and New Yorker publishers for lowering the bar, or movie audiences and readers for allowing them to lower the bar (or are we really just getting dumber that it wouldn't be beneficial for Hollywood and publishers to try to raise the bar up anymore than what it already is)? Is James Patterson a major success because he writes great novels, or is he a major success because the bookstores make sure his new book is the very first one you see when you walk inside the door, the only option you have in the small airport bookstore while you're waiting for your flight, etc.?

Who knows, and quite frankly, who cares?

What you should care about, if you want to break into traditional publishing, is just what Borders apparently owes publishers:

That's a lot of moolah there, no? And in the end, who is going to suffer first, the publisher or the writer?